EM Connectomics#

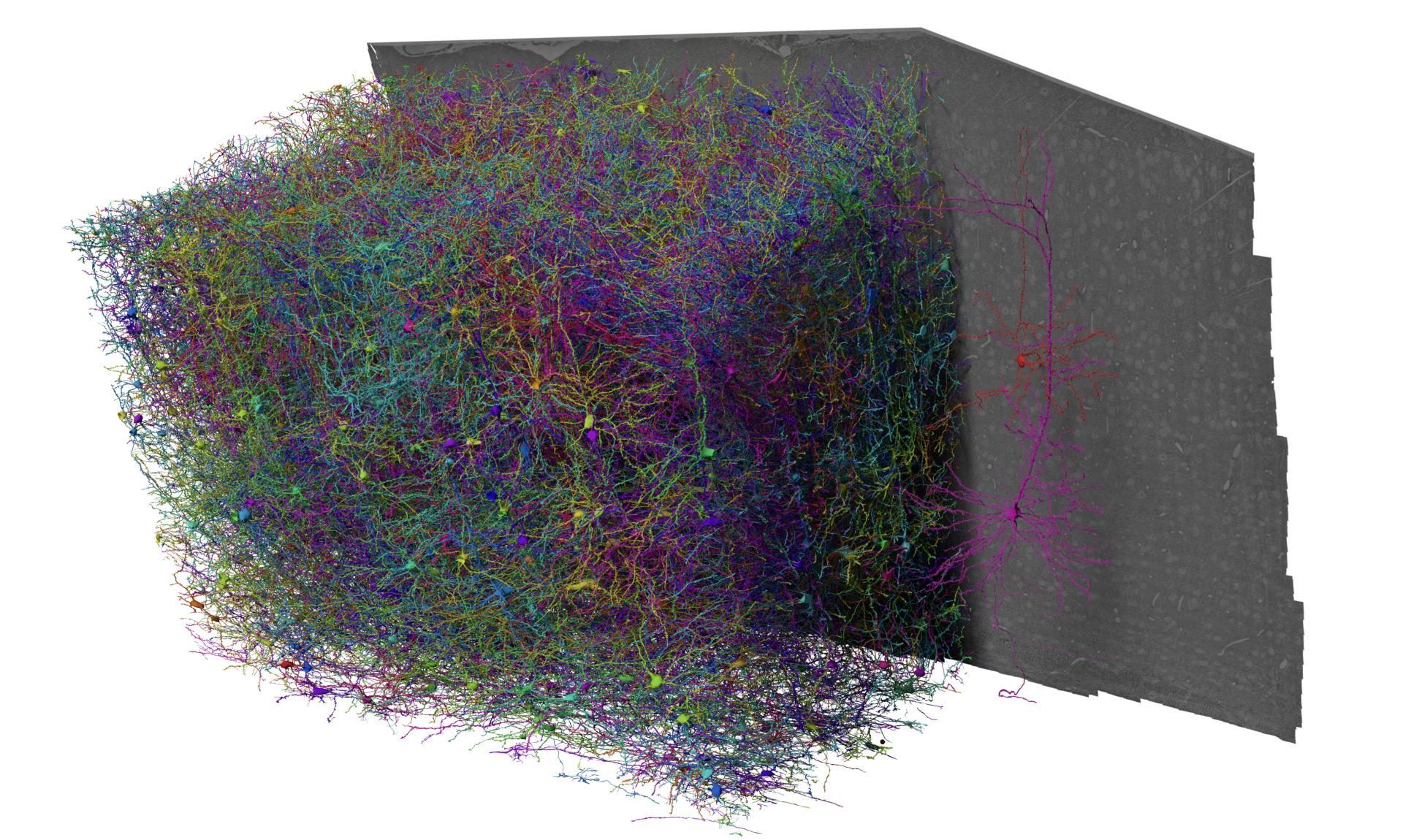

Fig. 12 A 3D rendering of cells in the MICrONs dataset.#

Background#

The function of the nervous system arises out of a combination of the properties of individual neurons and the properties of how they are connected into a larger network. The central goal of connectomics is to produce complete maps of the connectivity of the nervous system with synaptic resolution and analyze them to better understand the organization, development, and function of the nervous system. Electron microscopy (EM) has been a central tool in achieving these aims for two key reasons: 1) EM can easily image nanometer-scale structures such as synapses. This allows one to unambiguously observe chemical synapses and, if pushed to high enough resolution, gap junctions. (Note that the MICrONs dataset is not high enough resolution to unambiguously observe gap junctions.) 2) Dense staining methods allow the complete observation of a of rich collection of cellular features, including membranes, nuclei, mitochondria, and much more. This allows the reconstruction of the complete morphology of cells.

The general approach to EM involves staining tissue with heavy metals and using electrons to imaging thin sections of tissue. Sections can either be created by cutting tissue into slices (“serial section”) followed by imaging, or by imaging the face of a block and shaving off a thin layer of tissue after each run (“block face”). In both approaches, each section corresponds to only 30–50 nanometers of thickness (although it can be a millimeter wide), and thus assembling a substantial volumes involves thousands or tens of thousands of sections in a row. Finally, computational methods are used to align and assemble the sections into a single volume and then to segment the volume into individual cells and synapses.

While the resolution afforded by EM has been used to study the nervous system since 1959, the first true “connectomics” project that merged dense mapping of neurons and synaptic connectivity was the study of the nematode C. elegans led by Sydney Brenner, John White, and others. Advances in EM methods and computational methods in the last ten years have allowed tremendous scaling of connectomics datasets. The largest current mammalian datasets, including the MICrONs volume will consider here, now span more than a cubic millimeter, and invertebrate datasets now can cover the entire brain of a fruit fly.

What questions can be addressed by connectomic datasets?#

For invertebrates like the fruit fly, the nervous system is highly stereotyped in both the composition of cells and how they connect to one another. Indeed, in the fly many cell types exist as a single pair of cells, one from the left and one from the right hemisphere. Connectomic maps from one individual can thus act as a nearly universal map of the brain and powerfully inform theoretical and experimental studies.

In mouse cortex, this same type of stereotypy does not apply. There is no one-to-one match between any given cell in the brain of one mouse and another, and thousands of cells in a cortical area can belong to the same cell type. Because of this, the types of questions one can ask differ, but dense reconstruction of anatomy and connectivity still can be a powerful source of insight into questions like:

What morphological or connectivity-based cell types can be found?

What are the properties of the excitatory networks in cortex and how might they relate to learning rules?

What rules dictate how inhibitory cells distribute their synaptic output across target cell types?

In some datasets, such as the MICrONs dataset, calcium imaging of the same tissue was performed prior to preparing the structural EM volume. In that case, we can address additional questions like:

How do functional responses relate to the morphology of cells?

How do functional responses relate to the connectivity of cells?

In addition, a whole host of non-neuronal cells are also present, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and pericytes. Many people are interested in studying the relationship between these cells and neurons, and connectomic datasets can be a powerful tool to discovery this structural context.

The MICrONs dataset#

Note

For more complete details about the generation of the volume, please see Schneider-Mizell et al. [2023].

The MICrONs dataset is an EM volume of mouse visual cortex that spans all cortical layers, and extends approximately 1 mm in width by 0.5 mm in depth, collected as a collaboration between the Allen Institute for Brain Science, Baylor College of Medicine, and Princeton University. The goal of this dataset was to produce a so-called “functional connectomics” volume, where the same population of neurons could be measured with both calcium imaging to record functional properties and EM to describe synapse-resolution structural properties.

To link structure and function, excitatory neurons were genetically labeled with GCaMPs and imaged under a battery of natural movies and parametric stimuli by the Tolias lab, then at Baylor College of Medicine. The mouse was shipped to the Allen Institute and the same cortical region was prepared for EM, with more than 25,000 sections cut from the block and imaged across a small fleet of electron microscopes. In order to capture the interactions between different visual regions, the volume location is at the edge of primary visual cortex and extends into higher visual areas AL and RL [Glickfeld and Olsen, 2017]. Imagery was then aligned and segmented by the team of Sebastian Seung at Princeton, who also automatically detected synapses and nuclei. A team of proofreaders at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory helped correct the largest types of errors in the segmentation, leaving virtually every neuron as a distinct object, and coregister tens of thousands of neurons to the functional data. Further analysis at the Allen Institute and elsewhere has focused on curating a map of cell types across the entire dataset, and generating a database to link synapses, cell types, and more to the morphology of individual cells.

The result is a cubic millimeter scale dataset with a rich collection of information and the potential for a range of studies, with strengths and limitations due to the current state of proofreading and needs of the functional data collection.

The next sections of the Data Book will introduce how to access the various parts of the dataset and give some guidance about how to use them.