Meshes#

When trying to understand the fine 3d morphology of a neuron (e.g. features under 1 micron in scale), meshes are a particularly useful representation. More precisely, a mesh is a collection of vertices and faces that define a 3d surface. The exact meshes that one sees in Neuroglancer can also be loaded for analysis and visualization in other tools.

Downloading Meshes#

The easiest tool for downloading MICrONs meshes is Meshparty, which is a python module that can be installed with pip install meshparty.

Documentation for Meshparty can be found here.

Once installed, the typical way of getting meshes is by using a “MeshMeta” client that is told both the internet location of the meshes (cv_path) and a local directory in which to store meshes (disk_cache_path).

Once initialized, the MeshMeta client can be used to download meshes for a given segmentation using its root id (seg_id).

The following code snippet shows how to download an example mesh using a directory “meshes” as the local storage folder.

import os

from meshparty import trimesh_io

from caveclient import CAVEclient

client = CAVEclient('minnie65_public')

mm = trimesh_io.MeshMeta(

cv_path=client.info.segmentation_source(),

disk_cache_path="meshes",

)

root_id = 864691135014128278

mesh = mm.mesh(seg_id=root_id)

One convenience of using the MeshMeta approach is that if you have already downloaded a mesh for with a given root id, it will be loaded from disk rather than re-downloaded.

If you have to download many meshes, it is somewhat faster to use the bulk download_meshes function and use multiple threads via the n_threads argument. If you download them to the same folder used for the MeshMeta object, they can be loaded through the same interface.

root_ids = [864691135014128278, 864691134940133219]

mm = trimesh_io.download_meshes(

seg_ids=root_ids,

target_dir='meshes',

cv_path=client.info.segmentation_source(),

n_threads=4, # Or whatever value you choose above one but less than the number of cores on your computer

)

Note

Meshes can be hundresds of megabytes in size, so be careful about downloading too many if the internet is not acting well or your computer doesn’t have much disk space!

Healing Mesh Gaps#

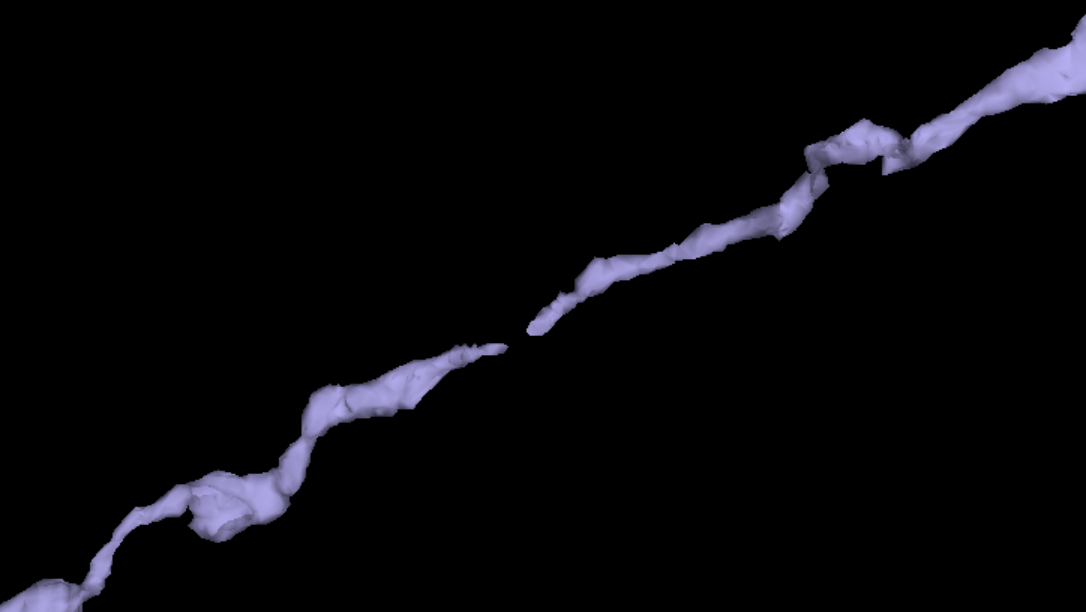

Fig. 26 Example of a continuous neuron whose mesh has a gap.#

Many meshes are not actually fully continuous due to small gaps in the segmentation. However, information collected during proofreading allows one to partially repair these gaps by adding in links where the segmentation was merged across a small gap. If you are just visualizaing a mesh, these gaps are not a problem, but if you want to do analysis on the mesh, you will want to heal these gaps. Conveniently, there’s a function to do this:

mesh.add_link_edges(

seg_id=864691134940133219, # This needs to be the same as the root id used to download the mesh

client=client.chunkedgraph,

)

Properties#

Meshes have a large number of properties, many of which come from being based on the Trimesh library’s mesh format, and others being specific to MeshParty.

Several of the most important properties are:

mesh.vertices: AnN x 3list of vertices and their 3d location in nanometers, whereNis the number of vertices.mesh.faces: AnP x 3list of integers, with each row specifying a triangle of connected vertex indices.mesh.edges: AnM x 2list of integers, with each row specifying a pair of connected vertex indices based off of faces.mesh.edges: AnM x 2list of integers, with each row specifying a pair of connected vertex indices based off of faces.mesh.link_edges: AnM_l x 2list of integers, with each row specifying a pair of “link edges” that were used to heal gaps based on proofreading edits.mesh.graph_edges: An(M+M_l) x 2list of integers, with each row specifying a pair of graph edges, which is the collection of bothmesh.edgesandmesh.link_edges.mesh.csgraph: A Scipy Compressed Sparse Graph representation of the mesh as anNxNgraph of vertices connected to one another using graph edges and with edge weights being the distance between vertices. This is particularly useful for computing shortest paths between vertices.

Important

MICrONs meshes are not generally “watertight”, a property that would enable a number of properties to be computed natively by Trimesh. Because of this, Trimesh-computed properties relating to solid forms or volumes like mesh.volume or mesh.center_mass do not have sensible values and other approaches should be taken. Unfortunately, because of the Trimesh implementation of these properties it is up to the user to be aware of this issue.

Visualization#

There are a variety of tools for visualizing meshes in python. MeshParty interfaces with VTK, a powerful but complex data visualization library that does not always work well in python. The basic pattern for MeshParty’s VTK integration is to create one or more “actors” from the data, and then pass those to a renderer that can be displayed in an interactive approach. The following code snippet shows how to visualize a mesh using this approach.

mesh_actor = trimesh_vtk.mesh_actor(

mesh,

color=(1,0,0),

opacity=0.5,

)

trimesh_vtk.render_actors([mesh_actor])

Note that by default, neurons will appear upside down because the coordinate system of the dataset has the y-axis value increasing along the “downward” pia to white matter axis. More documentation on the MeshParty VTK visualization can be found here.

Other tools worth exploring are PyVista, Polyscope, Vedo, MeshLab, and if you have some existing experience, Blender (see Blender integration by our friends behind Navis, a fly-focused framework analyzing connectomics data).

Masking#

One of the most common operations on meshes is to mask them to a particular region of interest.

This can be done by “masking” the mesh with a boolean array of length N where N is the number of vertices in the mesh, with True where the vertex should be kept and False where it should be omitted.

There are several convenience functions to generate common masks in the Mesh Filters module.

In the following example, we will first mask out all vertices that aren’t part of the largest connected component of the mesh (i.e. get rid of floating vertices that might arise due to internal surfaces) and then mask out all vertices that are more than 20,000 nm away from the soma center.

from meshparty import mesh_filters

root_id =864691134940133219

root_point = client.materialize.tables.nucleus_detection_v0(pt_root_id=root_id).query()['pt_position'].values[0] * [4,4,40] # Convert the nucleus location from voxels to nanometers via the data resolution.

mesh = mm.mesh(seg_id=root_id)

# Heal gaps in the mesh

mesh.add_link_edges(

seg_id=864691134940133219,

client=client.chunkedgraph,

)

# Generate and use the largest component mask

comp_mask = mesh_filters.filter_largest_component(mesh)

mask_filt = mesh.apply_mask(comp_mask)

soma_mask = mesh_filters.filter_spatial_distance_from_points(

mask_filt,

root_point,

20_000, # Note that this is in nanometers

)

mesh_soma = mesh.apply_mask(soma_mask)

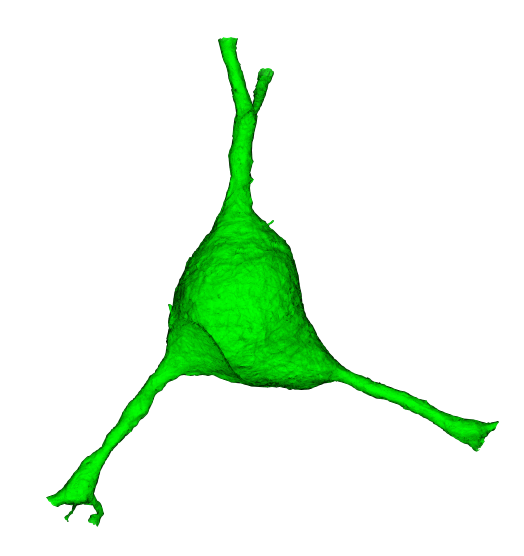

This resulting mesh is just a small cutout around the soma.

Fig. 27 Soma cutout from a full-neuron mesh.#