Dynamic Foraging#

At the Allen Institute for Neural Dynamics, we are interested in understanding:

How experience drives learning.

How behavioral strategies (policies) are stored, maintained, and updated.

How movements are generated from behavioral policies.

How brain-wide neural circuits are organized and operate: networks within areas, across areas, and regulation of information flow by neuromodulators.

We develop behavioral tasks that give us access to neural dynamics across brain regions, with cell-type specificity over multiple timescales. This requires a careful balance of tight task control that also respects the ethology by tapping into evolutionarily relevant behaviors across mammals, including mice. We focus on tasks that are amenable to quantitative modeling, including rich theories from reinforcement learning and foraging (Stephens and Krebs, 1987; Bertsekas and Tsitsiklis, 1996; Sutton and Barto, 1998; Houston and MacNamara, 1999).

Dynamic Foraging Task#

We first must define a set of requirements for a task that addresses our research goals. An ideal task satisfies these requirements:

Reproducible behavioral performance across mice

Rapid task acquisition

Scalable

Changes in the environment that require the animal to learn from experience

A limited set of choice movements, allowing us to correlate movements with neural activity

Amenable to modeling that explains behavior

The dynamic foraging task was designed to meet these criteria. It has two alternative choices, binary reward, and nonstationary reward probabilities given each action. A rich literature in animal learning theory, psychology, and—more recently—neuroscience, has shown this to be a fruitful task. We took inspiration from earlier experiments in monkeys (Sugrue et al., 2004; Lau and Glimcher, 2005; Tsutsui et al., 2016) to develop an analogous task for mice (Bari et al., 2019; Hattori et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022).

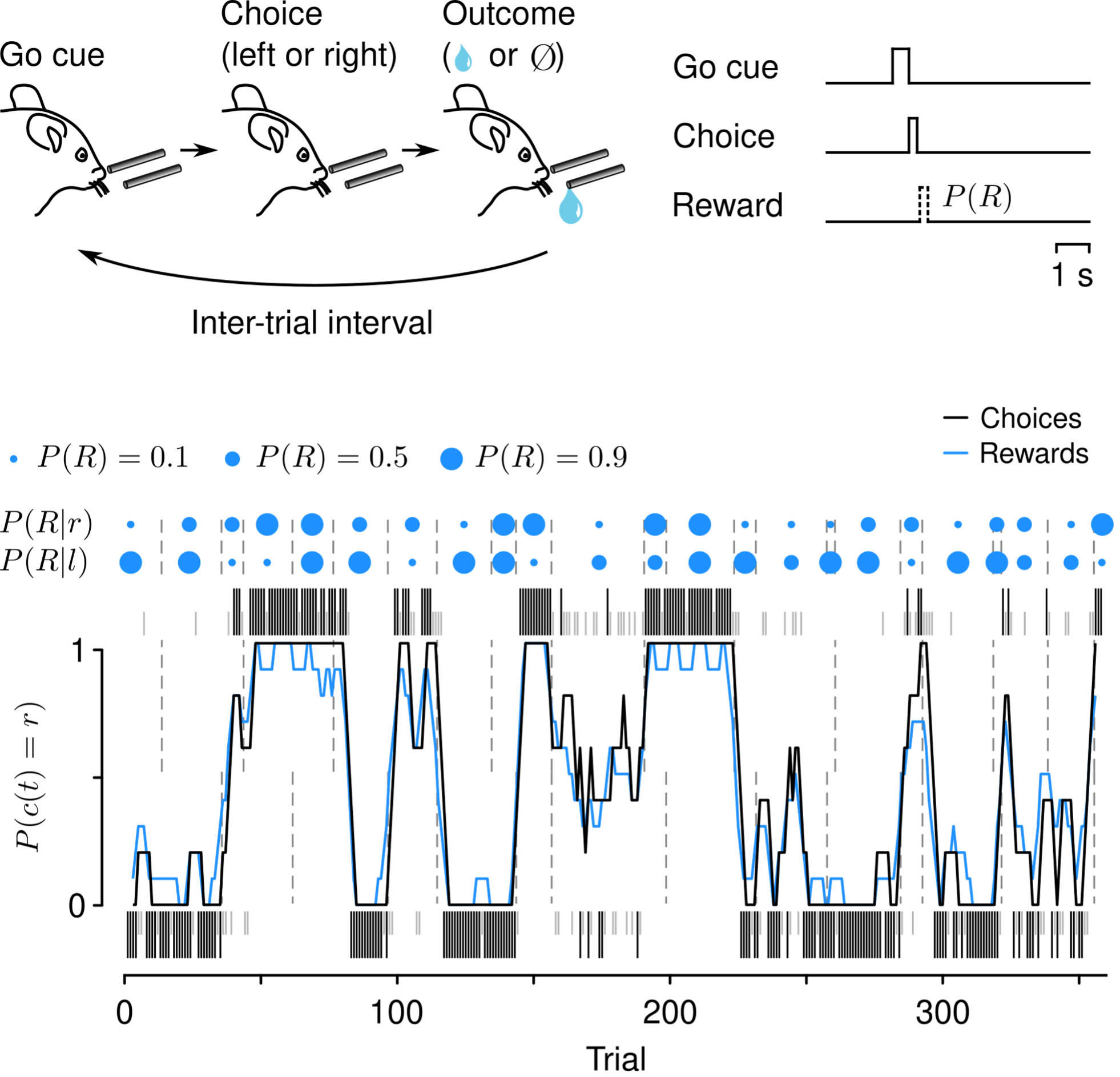

In our experiments, thirsty, head-restrained mice perform hundreds of trials each day. A trial begins with an auditory “go” cue, after which mice have a short window in which to lick toward a leftward or rightward tube. Choices are followed by either a water reward or no outcome. Reward probabilities are assigned to each tube and vary over the course of a session.

Fig. 1. Top, cartoon of behavioral task events. Bottom, behavioral data from an example session. Dots above the plot correspond to reward probabilities given leftward (P(R|l)) or rightward (P(R|r)) choices. Ticks correspond to choices to the left (below) or right (above) that were rewarded (black) or unrewarded (gray). The black curve is a running average of the mouse’s choices leftward or rightward. The blue curve is a running average of the reward available from the left or right. Note that the mouse’s choices closely follow the reward dynamics.

A critical feature of this task is that it allows us to study learning in real time: mice adjust their behavior as reward probabilities change. There are several parameters that govern how the reward probabilities change over time. We manipulate two in particular: whether reward probabilities on the left and right sides change at the same time (“coupled”) or independently (“uncoupled”) and whether the reward from a choice is available regardless of the mouse’s choice (“baiting”). Baiting is defined such that if an unchosen action would have been rewarded, the reward is delivered upon the next choice of that alternative.

Fig. 2. Left, training curriculum for the dynamic foraging task. Right, task parameters for each stage. See below for definitions.

Statistical analysis of dynamic foraging behavior#

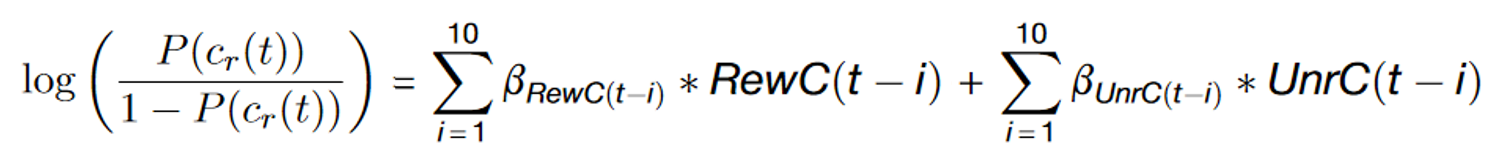

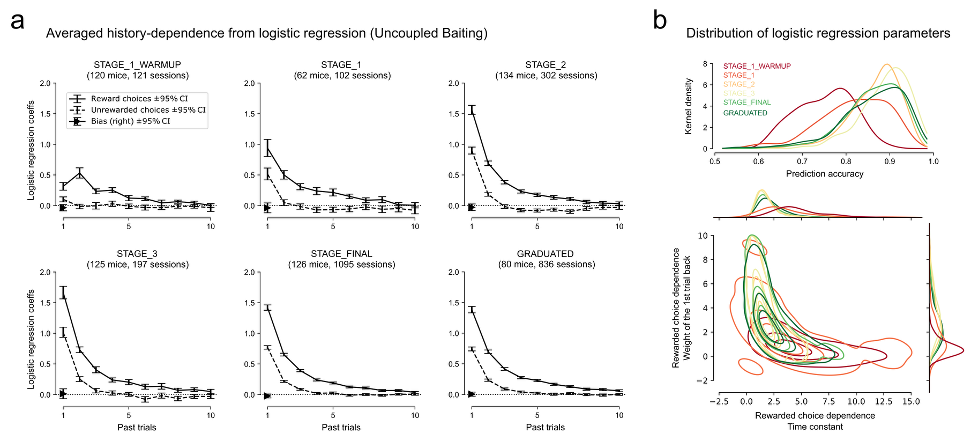

The central hypothesis for how mice behave in the dynamic foraging task is that they use recent actions and outcomes to change future behavior. One simple analysis that demonstrates mice use recent actions and outcomes is a logistic regression model that uses past rewards and choices to predict the future left/right choice.

Fig. 3. Reward-history-dependent learning within and across sessions. (a) Regression coefficients develop over training stages and display exponential weighting as a function of trial history. (b) Reward-history-dependent learning evolves smoothly across learning stages.

Reinforcement-learning models#

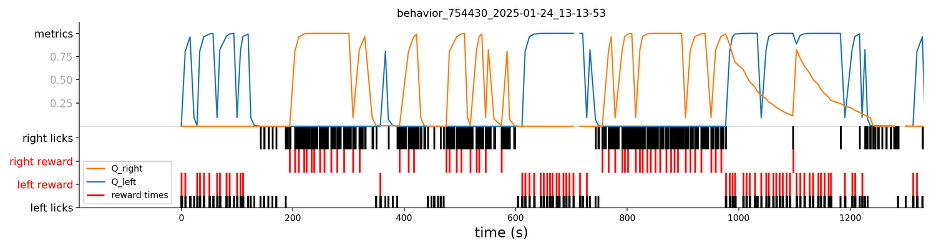

Reinforcement-learning models are useful for inferring the “hidden” variables that a mouse may use while engaged in the foraging task. This is especially true when paired with statistical analyses. For example, Fig. 3 shows that mice use reward history to guide future choices. What might be the mechanism underlying this type of learning? One possibility is that the brain generates errors: discrepancies between the predicted and observed outcomes of actions. This can be formalized in a reinforcement-learning model, whose extracted latent variables can subsequently be linked to neural activity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Example session with fitted Q values for left (blue) and right (orange) choices. Below the Q values we show that animal’s licks (black) and whether or not the lick was rewarding (red). The Q values fitted here use a reinforcement-learning model (Q-learning) with 2 learning rates (each one for positive and negative RPEs), a choice kernel to address side bias, and softmax function for determining choice.